Fashion’s Obsession: Why The Industry Lives in the Past

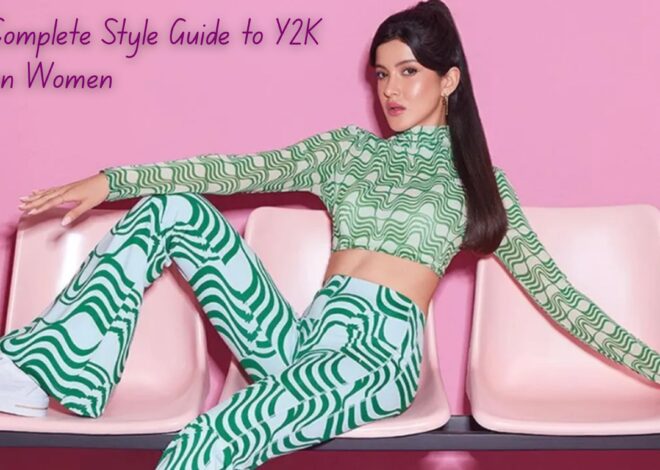

The world of fashion is an interesting paradox. Although it is constantly promoted as a predictor of future trends and a harbinger of cultural change, the engine of the industry is constantly fueled by nostalgia. Every season, designers, marketers and critics turn their gaze backward, reviving decades-old silhouettes, textures and moods. From the widespread return of ’90s minimalism and the Y2K aesthetic to the enduring appeal of ’70s bohemian chic and ’50s glamour, fashion often feels less like an innovator and more like a skilled curator of historical styles.

Why does an industry supposedly obsessed with the “new” remain fundamentally in the past? This deep dive explores the psychological, economic, and cultural forces that force fashion to endlessly repeat its history.

🧠 The Psychology of Nostalgia: Comfort and Cultural Cycle

The most powerful driver of fashion’s backward glance is the human brain’s fascination with nostalgia – a bittersweet longing for the past. This isn’t just a marketing ploy; It is a deeply rooted psychological need.

1. The Comfort of the Known

Fashion cycles often peak at times of significant social, political or economic uncertainty. When the present seems unstable, consumers instinctively gravitate toward styles of the perceived “simpler” or more stable past.

- Emotional Anchor: For many adult consumers, retro fashion is literally tied to their youth or childhood – a time associated with fewer responsibilities and more innocence. Wearing flared jeans or an oversized blazer from a bygone era provides a real emotional anchor in an uncertain world.

- Safety in Familiarity: Newness in fashion can feel alienating or intimidating. Genres that have already had their moment have been subjected to cultural scrutiny; They are safe, recognizable and easy to integrate into a modern wardrobe, without the risk of looking “out of place”.

2. The 20-Year Rule (or 30-Year Rule)

The fashion cycle operates with a predictable rhythm, often summarized by the 20-year rule. This theory states that it takes about two decades for a trend to become fashionable again.

- Why 20 years? A gap of 20 to 30 years keeps this revived trend out of the shopping and cultural memory of the current generation of young consumers (teens to mid-twenties). They consider this style to be innovative and attractive, free from the burden of being “old” or “outdated”. Additionally, this trend appeals directly to consumers in their 40s and 50s who are experiencing the style for the first time – the demographic that often holds the most purchasing power.

- Second-hand experience: Today’s obsession with Y2K (early 2000s) coincides perfectly with this rule, attracting Gen Z who are encountering low-rise pants and tiny sunglasses for the first time as adults.

💸 The Economics of Resurrection: De-Risking Design

For multi-billion dollar corporations, introducing entirely new silhouettes or revolutionary textile processes carries enormous financial risk. Leveraging the past offers a practical, low-risk approach to design and manufacturing.

1. Validated Demand and Proven Success

Reviving a previous trend is a form of market validation. Designers know that certain styles (like the A-line skirt, trench coat, or punk aesthetic) have successfully sold to millions of people over the past decades.

- Estimated ROI: Instead of betting on an unproven invention, a designer can refine a proven hit. They update the fit, change the textile technology, or adjust the context, but the basic silhouette – the element that requires the most complex manufacturing retooling – remains familiar, ensuring a high potential for return on investment (ROI).

2. Efficiency in Manufacturing and Sourcing

Innovation is expensive. Recycling styles are efficient. The global supply chain is already adapted to producing certain cuts and materials that were popular in the past.

- Pattern blocks and molds: Factories retain pattern blocks, molds, and machinery specifications for popular historical items. Reviving a 1980s power shoulder or a 1960s shift dress is simply a matter of removing existing templates, which saves significant time and cost in research and development.

- Inventory management: When a trend is successfully recycled, brands can strategically use archival imagery and even existing deadstock materials, reducing waste and (obviously) contributing to a circular economy narrative.

3. The Power of Differentiation Through History

In a saturated marketplace where everyone has access to the same technology, history is one of the few ways a luxury brand can truly differentiate itself.

- Heritage Branding: Houses like Chanel, Dior and Hermès don’t just sell clothes; They sell history. Their constant reference to their founders’ original works (Chanel tweed jacket, Dior New Look) reinforces their heritage and distinctiveness. The past serves as an insurmountable barrier to entry for fast-fashion competitors, who may copy the style but never the heritage.

🌐 Cultural Context and Modern Curation

Fashion is a mirror of culture, and in the digital age, our relationship with history has fundamentally changed. The Internet has turned the past into a vast, searchable, and ever-present mood board.

1. The Archive is Omnipresent

Before the Internet, fashion history was limited to runway shows, magazines, and expensive reference books. Today, every outfit ever worn, every runway show ever staged, and every cultural artifact is instantly accessible through platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok.

- Democratization of inspiration: This constant flow of archival imagery means that inspiration is no longer determined by just a few top designers. A random vintage image of a 1970s celebrity or obscure subculture can go viral, creating instant demand and forcing designers and retailers to respond with new product lines.

- Styling as a History Lesson: Modern influencers and stylists are essentially historians, teaching their followers how to reinterpret looks from different eras, thereby fueling the cycle of revival.

2. Identity and Subculture Blending

In the past, trends often moved linearly. Today, subtle trends and aesthetic blending are key. The Internet allows consumers to simultaneously adopt looks from different decades – mixing a 1990s slip dress with 1980s sneakers and 2000s cargo pants.

- Postmodern Collage: This is the essence of postmodern fashion: a collage of historical references drawn to create a highly personal, non-linear identity. Fashion designers respond by offering comprehensive, historically informed collections that cater to these diverse, digitally informed tastes.

3. Sustainability and The Vintage Movement

The growing movement toward sustainable consumption has inadvertently reinforced fashion’s dependence on the past.

- Vintage Value: Consumer preference for second-hand, vintage, and affordable clothing directly increases the value of vintage styles. Brands respond by creating new pieces that mimic the desirable quality and shape of those vintage items, bridging the gap between historical appeal and modern manufacturing.

⏭️ Conclusion: The Future of Fashion is Iterative

Fashion’s obsession with the past is not a sign of creative failure; It is an acceptance of human nature, economic practicality and cultural richness. Industry operates not by constant reinvention, but by iterative refinement.

Designers aren’t just copying; They are engaged in a constant dialogue with history, asking: How can we make the proven beauty of the past feel relevant and essential to today’s consumer?

The next major trend won’t be completely unknown; It will be a familiar shape, texture or mood, re-imagined for a new generation – perhaps the exaggerated power shoulders of the 2010s, or the extreme athleticism of the mid-2020s, ready for their 2040 close-up. In fashion, the only way forward is often to look back.